| Design | ||

| Modifications | ||

| Development | ||

|

[04-FEB-26] Below you will find circuit diagrams, data sheets, and other design files for the A3054 assembly. All our designs are free and open-source, with copyright protection presented in the GNU Public License, Version 3.0.

[04-FEB-26] None yet.

Chronological record of the development and production of the implantable Blood Pressure Monitor (A3054).

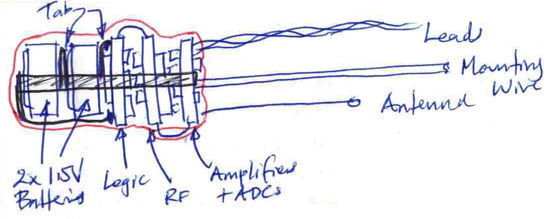

[04-FEB-26] Create web pages. Here is a sketch of the planned three-layer PCB rigid-flex circuit. The board consists of three circular sections joined by two flex cables. The flex cables between the rigid sections are just the right length so that they allow the rigid sections to fold over onto one another without leaving extra flex cable to jut out the side of the implant. On either end there are flex cables with flex connectors at the end. We use the left flex cable to power the circuit and program the logic chip. We use the right flex cable to test the amplifiers.

From left to right we have Section I, Section II, and Section III. Each lies within a 10-mm diameter circle and is squared off where the flex cable emerges from its side. The positive and negative battery tabs are on Section I. We tab-weld two 1.5-V SR936 1.5-V 9.5-mm diameter, 3.6-mm thick, 75 mAhr batteries together and to these two tabs to power the circuit, with the positive terminal resting on the logic chip and the negative terminal of the second battery on top. The two batteries are connected by their own tab. We cannot trust to contact to hold them together because the epoxy of encapsulation will penetrate between the two of them. Later, we fold the circuit onto itself, and secure the three layers together by tab-welding the two longer tabs on Section III to the negative terminal of the top battery.

Section I holds the magnetic sensor and transistor that put the circuit to sleep, the logic chip, a buck converter to generate the 1V2 logic power supply voltage, a linear regulator that produces 1.8 V, BMA423 accelerometer, TMP117 temperature sensor, and a converter that provides a battery voltage measurement.

We have a long discussion with ChatGPT about the possibility of using other logic chips, or ready-made micropower MCUs in place of our OSR8 in LCMXO2 FPGA. We consider using in place of the OSR8 the open-source PicoRV32 VHDL processor. This thirty-two bit alternative to our eight-bit processor takes up two thousand LUTs in its usual form, but can be stripped down to 750 LUTs, although in this state it has no memory interface. We consider how long the PicoRV32 will take to perform typical IPT tasks, such as add and accumulate samples, respond to interrupt, and generate random number. We estimate the PicoRV32 will take at least twice as long to perform these tasks, doubling our dynamic current consumption. An advantage of the PicoRV32 is the C-compiler toolchain we can use with it, but we enjoy writing OSR8 assembler, so we have no problem living without a compiler. Another big issue for the implant is the calibrated ring oscillator that turns on and off instantly. These are not available in any existing MCUs, which use RC oscillators, and none of the RC oscillators in the PIC chips we looked at will run at 5 MHz, only 4 or 8 MHz on either side. Our conclusion was that our existing LCMXO2, ring oscillator, and OSR8 is already the most energy-efficient design.

We would like to have spare logic on our device, but at the same time we want to get moving with a flex circuit that does not require microvias to transport IO signals out of a dense BGA. We decide to start our development of the IPT with the LCMXO2-1200ZE in QFN-32, which provides 21 IO pins, enough for the design we have in mind, and is easy to load by hand and work with. Despite the use of this larger package, we expect to be able to load a 1.2-V buck converter using made out of the ST1PS02D, its inductor and decoupling capacitor, on one side of the board, along with a 1.8-V linear regulator. The 1V8 will be used to power the accelerometer and temperature sensor, as well as the logic interfaces of our analog to digital converters, and our antenna switch. The logic chip will have all its I/O pins running off 1.8 V. This is adequate to control our five-bit tuning DAC, the VCO control input, the PE4259 RF switch, and the logic interfaces on our ADS7052 converters.

Section II will hold all RF circuits, while passing through logic signals and power for Section III. We will place near the VCO the five-bit resistor DAC required to provide the VCO's tuning voltage. Also on Section II will be the antenna switch and the crystal radio that produces the received power signal RP. The antenna matching network will be placed between the VCO and the switch, and the switch directly on the antenna.

Section III will hold four amplifiers, each consisting of a single micropower op-amp such as the MAX4464 a few passives, and a ADS7052 converter. Three of the amplifiers, those intended for ECoG, will in addition be equipped with an AC/DC selectors switch DG2012E. Through-hole pads will accommodate up to six biopotential leads, an antenna, and a mounting wire we will use during encapsulation. We would also like to include on this board 2.0-V and 1.0-V linear regulators to provide the amplifiers and converters with clean analog power. By this means, we hope to eliminate the noise caused by the irregularity of our telemetry system's transmission scatter. The dedicated converters eliminate noise generated by selecting one of four analog voltages with an analog switch. A last function we wish to apply to Section III is an electrode impedance measurement with an analog switch that applies a −10 mV step to the ECoG reference potential.

The total surface area of these three boards, counting both sides, is roughly 220 mm2, compared to 150 mm2 for our rounded-corner 12.5-mm square A3049 printed circuit board, which houses two amplifiers with dual op-amps and 3-pole low-pass filters. Our hope is that with the increased area and reduced complexity of the amplifiers, we will be able to fit all IPT circuits on the three-part circuit board.

[06-FEB-26] Working on the A305401A layout. We can fit all the planned components on Section I with 10-mm diameter. We have yet to draw a circuit diagram or route connections.

[10-FEB-26] We have the P3054 repository set up on GitHub. We first worked on the P3041 firmware, fixing instability in its interrupt manager, making changes, recompiling and checking for stability. We create OSR8V4 and perform some consolidation of logic and renaming which, in the end, makes not difference to the compiled code. We start P3054 with P3042 V3.1. The code takes up 1267 LUTs. We reduce the millisecond interrupt timers from sixteen bits to eight bits. Now 1195 LUTs. Eliminate the clock calibrator, which includes an eight-bit counter that counts TCK periods. Our plan is to measure the TCK frequency by watching the state of RCK through the top bit of the status register, thus moving the counter into software. The code remains 1195 LUTs, despite the removal.

[11-FEB-26] We cannot fit all the components we need onto three sections 10-mm diameter along with the antenna mounting hole, lead mounting holes, and tab pads on Section III. We resolve to add Section IV. On this fourth section we place some 0.5-mm tall resistors and one analog switch. These will all be on the top-side of the PCB, which will be folded so that it becomes the end wall of the assembly. There will be no parts on the other side of this section. Now that we have more space, we will make thge rigid sections 0.6-mm thick, four-layer, rather than 0.8-mm thick six-layer. The flex sections will be 0.1-mm thick and two-layer.

The flex circuits at the either end are 11-mm side, terminated with a ten-way 1-mm pitch single-sided flex plug. The plug on the left carries the seven signals required to program the logic chip, plus three test point signals. The plug on the right carries all the analog signals, of which there are six, as well as the analog power supplies and the Receive Power (RP) signal. The antenna signal enters on Section IV, passes along the flex connector to Section III, passes through Section III, and so to Section II where it is delivered to the RF switch. The length of these tracks will constitute our antenna before encapsulation. After encapsulation, we have this path folded twice, and then a bent cable antenna outside.

Section I still holds the logic, buck converter, accelerometer, temperature sensor, and oscillator. Section II holds the tuning DAC, VCO, crystal radio, antenna switch, and also the four ADCs for the biopotentials. Section III holds the amplifiers and their AC/DC switches. Section IV has pads for mounting holes, and also the resistors that immediately greet the incoming ECoG signals, as well as the impedance-measurement switch and its pair of resistors. We have ample space for soldering leads into six through-hole pads, antenna into its own pad, and the mounting wire. After soldering these wires into Section IV, we trim the understide. We must avoid contact between these components and the parts on Section II. Because Section II will provide epoxy-encapsulated components 1 mm tall, the two boards will be 1 mm apart. The resistors on Section III will be 0.5-mm tall. So we must trim the back side of Section IV so that nothing sticks out by more than 0.4 mm, in order to avoid contact and allow epoxy to provide insulation between the sections. If we load the eight wires with Section IV pressed flat on a flat surface, we should be able to solder them from the top side and avoid any wire protrusion on the other side. All the mounting holes are large enough to allow solder to flow around the leads, antenna, and mounting wire.

Adding 0.6 mm of epoxy and silicone to the outside of the assembly, all allowing for some indentation between the circuit boards, we estimate total volume will be around 1.8 ml. We calculate the mass by adding the mass of the two batteries to the mass of the rest of the circuit, using for the rest of the circuit a density of 1.2 g/ml. We arrive at 3.2 g total mass. Battery capacity is 85 mAhr = 3500 μA·d at 3.1 V.

We add a 2K×8 EEPROM to Section I, an M24C16-F from STMicroelectronics. We connect this device to the same I2C bus we are using with the BMA423 accelerometer and TMP117 temperature sensor. All three devices are powered by 1V8 and share the same SDA and SCL. We now have two locations for non-volatile storate. The TMP117 contains 48 bits of general-purpose EEPROM, which we will use as the IPT's configuration EEPROM. We can use sixteen bits for the device ID, four bits for a ring oscillator calibration, four bits for an RF center frequency calibration, and eight bits for a battery capacity counter. We still have sixteen bits left for power-up configuration. We will use the M24C16's 2 KByte of EEPROM to store the IPT's activity program. This program is written in OSR8 assembler and manages the IPT's behavior when the IPT is active. Upon waking, or in response to a command, the IPT will copy the EEPROM into its own program memory. When we activate the IPT, it executes the activity program either 1024 times per second, depending upon the IPT's configuration. The activity program reads sensors, accumulates samples, and manages transmission of telemetry messages, including introducing temporal scattering. We note that executing 1024 times per second is about as often as we can hope to do so with the OSR8 running at 32.768 kHz. When the interrupt occurs, the OSR8 will complete its current operation (1), jump to the interrupt location (2), jump to the interrupt routine (3), push accumulator (1), load 0x01 (2), enable TCK (3), boost (3). So that's 15 clock cycles just to start the interrupt in boost. We need another 9 to return from the interrupt. So just servicing the interrupt without any content costs us 24 clock cycles, and we have only 32 between interrupts. Assuming our activity program completes in under 300 clock cycles, it will take 2 clock cycles, leaving 6 clock cycles for the main loop to use to service incoming commands. Somewhere in here we have to fit sample transmission and scatter.

[12-FEB-26] From our OSR8 study of static current consumption, we expect the static current drawn by one of the LCMXO2-ZE devices from our 3.0-V battery at 37°C to be 39% of the typical value presented in Table 3.9 of the MachXO2 data sheet.

| Device | LUTs | RAM KBits | I_q (μA) Tabulated | I_q (μA) Implantable | Packages (Name, mm × mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCMXO2-256ZE | 256 | 0 | 18 | 7.0 | QFN-32 5x5, ucBGA-64 4x4 |

| LCMXO2-640ZE | 640 | 18 | 28 | 11 | QFN-48 7x7 |

| LCMXO2-1200ZE | 1280 | 64 | 56 | 22 | WLCSP-25 2.5x2.5, WLCSP-36, 2.5x2.5, QFN-32 5x5 |

| LCMXO2-2000ZE | 2112 | 74 | 80 | 29 | WLCSP-49 3.2x3.2 |

| LCMXO2-4000ZE | 4320 | 93 | 124 | 48 | WLCSP-81 3.8x3.8, QFN-84 7x7 |

| LCMXO2-7000ZE | 6864 | 240 | 189 | 74 | NONE |

If we cannot fit our code into the 1200ZE, we will have the option of loading the 2000ZE in its place, and suffer an increase of 9 μA in our static quiescent current. For implants where we do not need the sophistication of the OSR8, such as an upgrade to our existing A3047, A3048, or A3049 SCTs, we could try the 256ZE with only 7 μA quiescent drawn from 3.0 V. Right now, the current consumption of the A3048 is 18 μA + 0.12 μA/SPS, of which 0.07 μA/SPS is the VCO during transmission, 0.01 μA/SPS is the DAC, 0.04 μA/SPS is the logic. The ADC contribution is negligible. If we add the quiescent current of the magnetic switch, op-amps, converter, and regulators, we might get 12 μA from the battery quiescent. Dynamic current consumption from logic will be at most that of an OSR8 plus ring oscillator, which is 1.2 mA * 7 μs = 0.0084 μA/SPS. Combined we get 12 μA + 0.09 μ/SPS. At 256 SPS this implies 35 μA. Operating life with CR1225 rises from the A3048's 41 days to 57 days.

[20-FEB-26] We have completed OSR8 V4.2. We removed eight instructions that we have never used. This size of the CPU by around 60 LUTs. We constrained the logic fully, adding default values for all signals in both combinatorial and synchronous processes. This increased the size of the code by around 100 LUTs. We removed integer types and replaced with unsigned and vector types. We simplified many expressions. We separated the ALU input multiplexer from the CPU into its own process. These changes reduced the size by around 40 LUTs. In the P3041 code, we fixed our asynchronous resets in the interrupt controller. We enhanced the boost controller so that it can start TCK and move immediately into boost. We added to the OSR8 an interrupt servicing output, which we now use to put the CPU immediately and automatically into boost when an interrupt starts, and out of boost when it ends. The P3041 code is now 1201 LUTs. We have 79 LUTs free. The A3054 does not need the A3041's sixteen-bit interrupt counters, nor its millisecond timer. It will not need the TCK calibrator because we have devised a way to calibrate TCK from within software by watching RCK and counting. When we remove these processes, the code shrinks by another 50 LUTs to about 1150 LUTs. We will have around 130 LUTs for A3054 peripheral functions, such as ADC readout.

[23-FEB-26] We are estimating the current consumption of the A3054. Suppose we digitize and accumulate samples from all four fourteen-bit ADCs at 1024 SPS. We now have instant boost and un-boost with FCK running for an average of 4 μs after we un-boost. We can ignore FCK current consumption outside the time required for completion of the interrupt. Using FCK to read out the ADCs, we can obtain a 14-bit sample in no more than 20 FCK cycles, or 2 μs. We estimate no more than 25 TCK clock cycles to read the sample and add to its 18-bit accumulator in RAM. We might be adding up to sixteen samples before transmitting. We use IX and IY to accelerate read and write. We have TCK = 5 MHz so that's 5 μs to read and accumulate. The read initiates the next conversion in the ADC. The ADC itself consumes 1 mA at 1 MSPS, so 1.0 μA at 1024 SPS. We have 7 μs of CPU in boost, consuming 1.2 mA from 1V2. With our 80% efficient converter, battery at 3.1 V, and 1V2 = 1.02 V, current from battery is 1.02 V / 3.1 V / 80% = 41% of 1V2 current. So our 1.2 mA is 490 μA from the battery. We need this current for 7 μs per sample per second, so 7 μs * 490 μA * 1/s = 3.4 nA/SPS = 3.5 μA to support 1024 SPS. Each active channel requires 1.0 + 3.5 = 4.5 μA for sampling.

At the end of the sampling interrupt we decide if we are going to transmit one of the channels. If we are going to transmit, we copy the 18-bit accumulator into an 18-bit transmit register and then shift left or right until we get the correct 16-bit sample. This might be the average of sixteen samples or a single 14-bit sample left-shifted twice so it is 16-bit. We set a random delay interrupt of 0-7 RCK cycles to produce transmission scatter. These tasks take another 25 clock cycles, or 5 μs, which is 2.5 nA/SPS transmitted. Our sample interrupt ends and the tranmit interrupt occurs a random time later. Right now, our boost controller does not allow us to leave boost during transmission. The transmission takes 7 μs at 10 mA from the battery directly for the VCO and about 10 μs at 1.2 mA from 1V2 for the CPU in boost. We have 7 μs * 10 mA * 1/s 70 nA/SPS for the VCO from the battery and 10 μs * 1.2 mA * 41% = 5 nA/SPS from the battery for the CPU, for a total of 75 nA/SPS transmitted.

The quiescent current of the LCMXO2-1200ZE at 37°C is 56 μA from 1V2. Add to this another 14 μA for the crystal radio, amlifiers, accelerometer, thermometer, and EEPROM, we get 70 μA. From the battery this will be 70 μA * 41% = 29 μA, say 30 μA. Combining this with the above 4.5 μA/Ch (per active input channel) and 75 nA/SPS transmitted we have:

I_a = 30 μA + 4.5 μA/Ch + 0.075 μA/SPS

Suppose we have one active channel at 256 SPS, our current is 53 μA, which is a little over the 48 μA maximum of the A3048S2. But here we are going to be adding four 14-bit samples to obtain a very fine 16-bit sample, far superior to the spikey sixteen-bit samples we obtain from the A3048. Now suppose we have two active channels at 512 SPS. Our current is 115 μA, which is less than the 22 + 1024 * 0.11 μA/SPS = 135 μA of the equivalent A3049 two-channel circuit.

[26-FEB-26] Schematic for A3054AV1 drawn. Parts arranged on A305401A printed circuit board.